Management of AHF:

Review of Contemporary Therapies and Current Guidelines

Review of Contemporary Therapies and Current Guidelines

J. Douglas Kirk, MD

Director, Chest Pain Evaluation Unit Department of Emergency Medicine, University of California, Davis, Medical Center, Sacramento, CA

I will continue this whirlwind tour through heart failure with basically covering some of the contemporary management strategies, as well as the current guidelines. As Frank alluded to, many of these guidelines are lacking and don't really hit the mark with respect to the acute management of heart failure that we see in the emergency department. The goals of therapy for ADHF are predominantly for us in the emergency department to relieve symptoms, and obviously that for the most part are patients who present with dyspnea, as Dr. Peacock has just described. We also want to attack the congestion that these patients have, both in the pulmonary vasculature, as well as in the systemic vasculature, predominantly with general edema.

We also want to improve hemodynamics. And again, this for the most part is really a target towards reducing left and right heart filling pressures because those are what have led to this pulmonary congestion and the symptoms that the patients typically present with. Improving cardiac output may be important, but it may not be important, as well. Peter may talk about this further in a moment. But that probably shouldn't be our predominant target as much as reducing filling pressures.

The most important thing that Frank just kind of gave you a little segue to this is that you need to do all this, but you can't hurt the kidneys because if you hurt the kidneys, you're going to kill the patient. And I think that's becoming more and more clear, and I'll show you some evidence to support that. So if you look at a number of studies that have looked at the relationship between worsening renal function and the management of ADHF, you'll see, whether or not you look at creatinine bumps of greater than .3 or .5, or increases in creatinines greater than 2, that all of these are related to an increase in mortality.

Forman and colleagues looked at 1,000 patients who were admitted with ADHF. This was a multicenter trial. And this was defined as a creatinine increase of greater than .3, and this was seen in about 27 percent of patients within just a short time after admission. And the particulars of this worsening renal function were probably what you'd expect in the most part: a prior history of heart failure. As we know, many people with heart failure continue to return with heart failure, and they have a gradual decline in both their function, as well as in their survivability from the subsequent admissions; if they had diabetes; or if they admission creatinines greater than 1.5; or in this study, in fact, a blood pressure that was exceedingly high. Those were all patients who had a sense -- or a more common sense of increasing their risk of renal dysfunction.

Regarding the relationship between this worsening renal function and hospital death, it is dramatically worse with an adjusted relative risk of approximately 7.5 for hospital death; a complicated hospital course was about twofold higher; and length of stay, which we all know is quite important to us in this era of resource management, was about threefold higher if these patients developed worsening renal function during this hospital admission.

We have numerous therapies that have been investigated, and we've identified a number of them that improve outcomes for heart failure patients when we use them for their management. But what you'll look here, whether you look at those that are associated with improved survival -- such as ACE inhibitors or ARBs or beta blockers or aldosterone antagonists -- or those that reduced hospitalization, what's the striking part of this is that these are none of the drugs that we use in the emergency department to treat heart failure. There really is no proven benefit to the things that we typically use, which I'll show you here in just a few moments, to treat heart failure. These really are all predicated and targeted at the outpatient chronic management of heart failure. And that's a real problem for us in the ED.

I'll give you a snapshot of what our current pharmacologic armamentarium is to treat these patients. It starts with diuretics. And most of us, if you look at the ADHERE database or any of the registries of heart failure, you'll see that a predominant tool for treating these patients are diuretic therapies. And that's really targeted to reduce the extracellular fluid volume. We use IV loop diuretics predominantly, but occasionally we'll use diuretics, such as metolazone or thiazides that affect the proximal tubule to effect a more rigorous diuresis, particularly if these patients have diuretic resistance and we're having to use exceedingly higher doses of loop diuretics to effect the same amount of urine output. Now, the problem with this is that it may unfavorably affect renal function. As we know, that might be tied directly to poorer outcomes.

We also use vasodilators to reduce filling pressure. This is predominantly true in those patients who present with acute pulmonary edema and are often quite hypertensive. The agents we use here predominantly are nitroglycerin, nesiritide to a lesser degree, and nitroprusside to a much lesser degree unless the patient is markedly, markedly hypertensive. We all know, or I suspect most of you know that there are safety concerns with at least one of these agents, nesiritide, which is certainly being investigated. And so it's kind of curtailed some of the use of that particular agent for this group of patients.

Last but certainly not least are the inotropes. Now, I think any of us who have trained back in the past 20 to 25 years, this was really the mainstay -- one of the mainstays of therapy, even for the patients that we typically see in an emergency department that don't have cariogenic shock.

We know now that there are substantial safety concerns with using inotropes to treat the garden variety, if you will, heart failure patient. And these consist of sympathomimetic agents that you're all familiar with, as well as some phosphodiesterase inhibitors. They're very effective if the patient has a frank low cardiac output state or cariogenic shock, but they're very ineffective and in fact can be harmful in the patients that don't have these presentations. And of course this only affects about 5 percent or so of the patients that we typically see in the emergency department. So they're really not a predominant tool for us to use currently.

If we hone down on the diuretics, we're going to see in the next couple of minutes here, I'm going to kind of pick on the drugs, if you will, and show you some of their weaknesses and what I think is fertile ground for further research and further investigation about what's the optimal use of these agents and in which particular patients. So if you look at diuretics, the thing that's interesting is that although with use them in great amounts, there really are no randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that show the efficacy of diuretics for the treatment of heart failure. That's very surprising I suspect for most of you. But what we do know is that there is pretty decent data that shows it actually impacts GFR in a negative way: It decreases it, it may activate neurohormones, it may cause re-accumulation of sodium, which often leads to diuretic resistance.

I'm sure everyone has seen this in your practice, or you've seen in your hospital us using exceedingly higher doses of diuretics to try to affect the same amount of diuresis in these patients. We give hundreds and hundreds of milligrams of furosemide at a time to try to squeeze those kidneys to get some urine out. And unfortunately that leads to negative effects in the long run for these patients. And that negative impact on clinical outcome actually can be both with the amount of resources you consume, but more importantly is actually that you can increase the mortality of these patients.

If you read heart failure literature or you go to any of these talks, you'll see this slide frequently. I think it's a great slide. This is a study by Gottlieb that looked at patients who got 80 milligrams of intravenous furosemide, which is not an uncommon dose, but a little on the high side for most de novo patients, but not uncommon. In fact, this is what most of our paramedic units use in the field for patients they suspect have ADHF. But they looked at these patients and they measured their GFR as a response to this versus placebo. And they also measured their urine output. And as you can see in the little box to the left, the placebo group had really little -- small change if any in the GFR, and really had no effect on urine output, whereas the IV furosemide, while it did effect a very brisk diuresis, about 1600 cc's of urine in eight hours, it also resulted in about a 20 percent drop in the GFR.

And as I showed you earlier, a drop in the GFR is not what we're trying to do with these patients. In fact, if you look at the study by Hasselblad, this comes from the ESCAPE database, this is a post hoc analysis that looked at the relationship between diuretic dose and mortality, you can see a pretty sharp increase in mortality in these patients treated with diuretics. You see the inflection point. It's really at a dose that most of us not uncommonly use: right around between 100 milligrams of furosemide up to around 200 milligrams. You can see a sharp increase in the mortality rate of these patients. So again, using high doses of diuretics to effect the treatment change that you're looking for -- i.e., a reduction in congestion -- may be good on the front end -- i.e., in the emergency department -- but you may be mortgaging the future of these patients on the back side because you've affected their renal function.

Moving on to vasodilators, again, these are very effective agents in people with high filling pressures, and again not particularly if they have significant hypertension. But nitroglycerin and nitroprusside are fraught with some difficulties in the management. Nitroglycerin can be very effective, but there are some side effects, it does require titration, tachyphylaxis or tolerance does develop fairly quickly with relatively small doses, so you have to continue to uptitrated, and then we all know of the concerns or problems with headache in these patients, as well. Nitroprusside is equally effective, but again, a very difficult drug to titrate because of its effect on the blood pressure, making patients hypertensive.

These often require ICU monitoring and frequently arterial lines. And it also has some negative impact on patients particularly if you have acute coronary syndrome that there may be some relationship with increased mortality in those patients who happen to have heart failure, as well. Nesiritide I mentioned earlier, very effective at lowering the wedge pressure, very effective at lowering -- improving dyspnea. But there is some concern that's currently being investigated about an increased signal of mortality and renal dysfunction. And the recently released FUSION-2 study by Clyde Yancy showed that it really had no favorable effect on mortality or renal function. You can look at that as the glass half-empty or the glass half-full. I would say it's actually half-full because the patients improved symptomatic-wise and there was no increased safety signal. So that was a good thing, I think, in the big picture. And again, this is being studied further under a current trial that's being investigated.

Inotropic therapy is likewise fraught with some complications, particularly increased mortality as well as aggravation of the arrhythmogenic potential for these patients, increasing heart rate and neurohormonal activations, as well. So again, these drugs while they can be quite effective in that cariogenic shock patient really don't have much role in the again garden variety patient with ADHF we see in the ED.

If you look at the broad scope of this problem, as I've already described to you, there's no good RCT data to support these drugs' use. And we've showed you that of all the drugs that improvement mortality, none of these drugs are really on the list. And while they might improve short-term prognosis, they may seem -- excuse me, short-term symptoms and signs, they may be related with long-term harm. I'm going to segue into the guidelines portion of this talk, and you'll see as we describe this there's really no universally accepted guidelines for the management of heart failure. That's true whether you look at the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), the Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA), or our own American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) guidelines, there's little consensus regarding the management. And this creates very inconsistent care. We know one of the things tied to outcomes is variability in treatment. So you don't want to have a broad range of therapeutic treatment in these patients because that leads to poorer outcomes.

We're trying to tie conclusive evidence to particular therapies to try to find out what works in what patients. And I'll tell you at the end of this talk about our efforts, as Frank alluded to earlier, from the Society's approach to managing these patients. If you look at the ACC/AHA guidelines, they really pertain to chronic heart failure and not acute decompensated heart failure. They really classify patients in ways that we don't -- really aren't even familiar and helpful to us: stage A, that they're at increased risk for heart failure versus stage D, and these are the patients with refractory heart failure, patients that need LVADs or need transplant to survive even for 30 days. So not very helpful in the acute world.

The European Society of Cardiology, again, if you look at the document, 80 percent of the document if not more really pertains to chronic heart failure management. There are some guidelines or recommendations for the acute management. And again, they've held a comparison to the chronic therapy. They do have some useful things as far as particular clinical scenarios -- and we're going to talk about that in a few moments -- that can help us try to be patient-specific with some of the recommendations.

The HFSA, a great organization that's addressing this problem, but again, if you look at the guidelines released in 2006, again predominantly regarding chronic management, there are some management recommendations, but they're not very patient-specific. They're very broad-based, and they're very -- they're not as useful for that honed down patient that we may see in the ED.

Last but not least, the American College of Emergency Physicians has recently published, in the last two years, a clinical policy statement regarding management, but it's very narrow in scope. In fact, it addresses four very specific questions. The first is the diagnostic use of BNP that Frank just discussed a few moments ago. And from a therapeutic side, it actually addresses the utility of noninvasive ventilation, diuretics, and vasodilators. And I'll go over those in just a second.

Now, as I said, there were four questions. This comes from the ACEP policy statement which was published in 2007. We'll focus on the last two: vasodilator use, as well as diuretic therapy. And the way these guidelines are set up is that they recommend things in three groups: Level A are recommendations that reflect a very high degree of clinical certainty; Level B is mild to moderate clinical certainty; and Level C really is expert panel consensus, so there's not a lot of good data to support a Level C recommendation.

So if you look at their comments on diuretics, the first thing you'll notice is there's no Level A recommendations because there's no good data. There are no RCTs that support their use. Now, from a Level B standpoint, some moderate certainty, they again in a broad sense recommend to treat patients with moderate to severe pulmonary edema with furosemide in combination with nitrate therapy. And a Level C recommendation is aggressive diuretic monotherapy, so by itself, is unlikely to prevent the need for intubation compared with aggressive nitrate therapy. Okay? And they also make a comment with respect to safety, that diuretics should be administered judiciously because of their association with renal dysfunction and the potential for long-term mortality.

Now, the vasodilator statement they made, again the thing you see quickly is that there really are no Level A recommendations again because no good RCT data from which to build from. They do have Level B recommendations, which are to administer an intravenous nitrate therapy, so nitroglycerin, to patients with acute heart failure syndrome who present with dyspnea. And then from a Level C standpoint, they actually -- they suggest not to use nesiritide instead of nitroglycerin because of the safety concerns, and that ACE inhibitors may be used, but you should be cautious about first dose hypotension. Very nondescript suggestions for the use of these agents in this group of patients.

We then move on to the Heart Failure Society of America's guidelines. These were published in 2006. And they make some broad statements regarding fluid and sodium restricted diuretic therapy, ultrafiltration, which I think Peter may talk about in a moment, vasodilator therapy, as well as inotropes. Now, their recommendations are similar in that they from a stronger standpoint they make the term -- use the term "is recommended" and then next down would be "should be considered" and then next down is "may be considered" and then last but no least is "is not recommended". But you can see how strong their statements are. So "is recommended" really is part of routine care, so it kind of sets the standard of care, if you will, in these patients. Their guidelines are again pretty short and sweet, but it is recommended that patients with AHF and increased fluid overload should be treated initially with loop diuretics given intravenously rather than orally, and it is recommended that diuretics be administered at doses needed to produce a rate of diuresis sufficient to achieve optimal volume status control and relief of signs and symptoms. So again pretty broad statements.

The other thing they do is that they kind of put all their eggs in a diuretic basket, at least on the initial management of patients, and that's irrespective of their presentation or hemodynamics. Now, they also go on to state that when congestion fails to improve with these diuretic therapies, you can add these other measures. So you can fluid restrict them, sodium restrict them, increase their doses of loop diuretics, so you can give a continuous infusion of a loop diuretic, or you can add one of those proximal loop diuretics to effect a great and more brisk diuresis. And then last but not least, ultrafiltration may be considered in these patients.

In the absence of symptomatic hypotension, you can use vasodilators. They can be considered in these patients, but again, lower level of evidence, B, and obviously frequency of blood pressure monitoring is recommended. And then you can use a combination of IV vasodilators and diuretics are recommended for rapid symptom relief. And these are the patients with acute pulmonary edema. So they present with acute symptoms. If they have pulmonary edema either on clinical exam or chest x-ray, those are important patients to use this combination of therapy. And then IV inotropes really are only indicated for those patients who have advanced heart failure and end-stage heart failure.

Moving on to the ESC guidelines, you can see just a quick snapshot here of what they recommend. They actually do recommend morphine, although Frank and I are both in agreement that this is not a very good drug for these patients for reasons that we'll be happy to discuss later because of the interests of time. Vasodilators are indicated. They're a Class 1 for nitroglycerin and Class 1 for nitroprusside. Nesiritide is not used in Europe, so it really has no recommendation. They don't recommend ACE inhibitors in Europe to be used acutely for these patients. They do indicate that diuretics are a very effective Class 1 recommendation. And again, beta blockers as you can imagine have a role but not again as much in the acute treatment of these patients. And inotropes are only recommended if they have hypoperfusion.

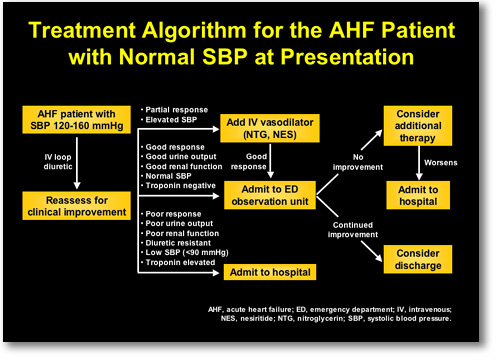

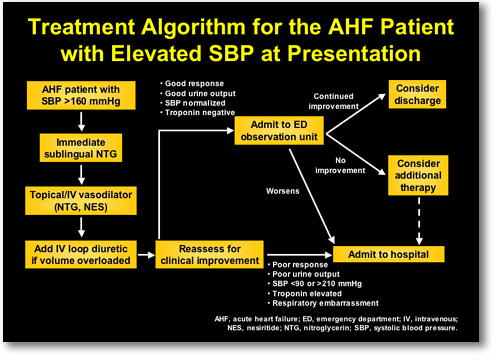

There are a group of folks that have kind of jumped off of the ESC guidelines and broken these into five different groups. And they treat them based on if the patient is hypertensive, hypotensive, or normotensive. And I think this is a very effective way. In fact, this is kind of similar to what we've done with the Society of Chest Pain Centers (SCPC) guidelines.

So the patients who present with hypertension and congestion, we use or we recommend the addition of noninvasive ventilation, nitrates as your first-line therapy, with diuretics to follow if the patients have ongoing signs of volume overload, whereas those patients who are normotensive, diuretics have more of a role, particularly if they are obviously volume overloaded, and again, those patients who are hypotensive we really don't recommend either of those agents. In fact, volume loading sometimes is helpful for these patients and obviously PA catheter management with inotropes is sometimes indicated.

They also go on to make comments about acute heart failure with acute coronary syndrome, and it really depends on what they present with for blood pressures. In the interests of time, I won't go into these in great detail. And then right ventricular heart failure very uncommon to present do novo by itself, but those patients typically if their blood pressure is high you can manage them with diuretic therapy; if it's low, often inotropes are indicated and needed to bail these patients out.

Now, my last slide here, and again, just to move forward, is just kind of an invitation to you, if you will, to come to our session this afternoon in the heart failure track, which will cover the guidelines that we produce. And this is a report from the Society of Chest Pain Centers. I was responsible just for the treatment guidelines. Frank Peacock, who spoke earlier, is the -- one of the co-chairs of the overall guidelines, and you'll hear us talk about from A to Z, all the guidelines and recommendations we'll make, and you'll see where we've taken these other guidelines and tried to meld them into a patient-centric useful guideline that you can use at the bedside for managing these patients.

And these are two of the graphics that we have, and we again break these up based on the patient's presentation, predominantly with their blood pressure at presentation (Figure 2). So I will just give you a little glimpse of this. This afternoon you'll see these.

|

FIGURE 2. Society of Chest Pain Centers Treatment Algorithm for the AHF Patient.

Top panel: Patients with normal systolic blood pressure (SBP) at presentation. Bottom panel: Patients with elevated SBP at presentation. |

|

In Summary; contemporary therapies are reasonably effective to relieve symptoms and congestion, but they may be associated with some deleterious effects. There may be some possible prognostic implications. Current guidelines are lacking with respect to management. No universally accepted approach. So hopefully the SECP guidelines will be very helpful, and please come to this afternoon's session and take a look at those. Thank you.

Dr. Peacock: So we have rapidly gone through the world of heart failure. Dr. Carson, Peter Carson, is from Georgetown. He's a cardiologist. This is the part of the meeting that I think is the coolest part because he's going to talk about what's coming down the pike. I think you learn more about physiology by seeing this kind of thing than a lot of the stuff that we've been talking about.

|