Future Directions in ADHF Treatment

Peter E. Carson, MD

Associate Professor of Medicine, Co-Director of Heart Failure Service, Georgetown University, Washington, DC

Thanks very much, Frank. It's a pleasure to be here this morning. It's a bit eye-opening to me, this meeting and this interaction between emergency rooms and heart failure. I was interested talking to Frank earlier that he and I had intersected at -- although not temporally, at Wayne State in Detroit, and I noticed one of the participants in the session this afternoon is from Detroit Receiving Hospital because when I was at Wayne State Hospital in downtown Detroit, in the emergency room at Detroit Receiving when I used to go down there from the CCU, frankly, if you hadn't been shot you hadn't been stabbed, there wasn't a whole lot of interest in you. So it's -- I'm delighted to see heart failure begin to take this place.

And I loved the last couple slides that Doug Kirk showed that indicated this interaction phase in the ER where you might take a patient with acute heart failure and work with the patient there to decongest them and treat them, and you might not even admit them, which expands then the role of emergency department observation units to the place where chest pain center and chest pain units are now developing, that you now have the potential for a heart failure unit, you may be able to treat a patient, make them better and not even have to admit them to hospital, and get them on the way to be able to receive the kind of chronic therapies that have been shown to be effective.

So from both speakers, let's just say that -- we're going to say that the diagnosis of heart failure has been established, a la Frank Peacock, so that's been already done. And Doug Kirk has already shown you many things about the -- both the limitations of what we know about what works in heart failure. So I'm just going to talk to you a little bit more in detail about those things that work or don't work, and why we think they do.

And Doug set the stage for me very nicely to be able to say currently nothing about dosage and side effects, which is not appearing on this slide here. But I'm just going to say to you that unfortunately diuretics, it's kind of like I look out at the audience, some of you are familiar with this comment that, you know, it's like teenagers: You can't live with them, and you can't live without them, with your teenaged children.

Diuretics are a lot like that. Patients come in, and they're congested. That is the vast majority of heart failure patients. They come in, they're congested, and you've got to do something about it then. And one of the problems that we have in terms of figuring out what works and what doesn't work is that the evaluation of what works is often seen in terms of what works over a long-term outcome -- 30 days, six months, a year -- based on what you had to do immediately in the emergency room. There's a bit of a disconnect there because lots of things then go bump in the night after a patient leaves the hospital that interferes with your ability to say what's good for a patient long term: So how do you prove that something really works has been a major problem for us.

The next slide shows a series of doses of diuretics that you all know to use. The only comments I want to make to you acutely is to say, "Sorry, folks, about the diuretics". I know they do bad things, but you've got to get the patient decongested and feeling better immediately in that -- soon after that 15-minute phase in the emergency room, and diuretics in the end are what you're going to use a lot. And the common mistake I see in our emergency room is that people don't give enough early, and they don't also repeat the dose. So remember that furosemide is going to have about a 15-, 20-minute, half-hour maximal onset of action. If nothing's happened by then and the patient is still congested, they're not doing well, give some more and maybe you're going to induce a diuresis.

Maybe you're going to improve symptoms on that basis and you're not going to end up having to do something like acutely intubating the patient. So an intubated patient that's alive is better than one that's dead, but on the other hand you want to be able to move quickly to avoid taking that kind of step. We do know that diuretics do have untoward effects. Doug Kirk said to you you see this slide all the time in heart failure talks, and you're going to see it twice this morning. This is from a study that Steve Gottlieb did looking at the effects of diuretics because he was comparing them to a new agent that I'll talk about in a moment, the adenosine antagonists, and Steve did indeed show that GFR did change in a negative direction with an 80 milligram dose of furosemide.

Now, the question of why that happens is kind of interesting: Is the molecule toxic to the kidney itself? Well, probably not. But what does happen is that if -- number two there is the afferent arterial, and the afferent arterial, if there's less blood flow through it to the glomerulus then you're going to find then that your GFR is going to drop. So if you drop volume by virtue of the diuretic then your GFR is going to drop because your flow through the kidney is dropping.

There's also this interest in the phenomenon of plasma refill rate, and that is the idea that as you pull fluid out of the vascular -- as you take fluid out of the vasculature, well, all that edema that you see on the patient's exam or the pleural fluid or the fluid within the abdominal cavity, well, that fluid then, that's excess fluid. You're trying to remove that fluid, and the idea is you're going to pull that out of the extravascular space and into the vascular space.

Unfortunately that doesn't always quite happen as the rate that you're pulling out of the vascular space, and so this concept of plasma refill rate is one of the things people talk about when you look at the GFR decreasing and the creatinine and the BUN going up, it's going up sometimes because you're not replacing what you've taken out of the vasculature from the third space.

It also was commented about the bad things diuretics do in other ways, particularly in neurohormonal stimulation. This is one of a couple studies, and maybe this is the best one that's shown that. It's an older study, goes back to the 1980s. This was published by a now colleague of Frank's, Gary Francis, who's now at the Cleveland Clinic. And what Gary did was to take a group of chronic heart failure patients and give them IV furosemide and to look at their hemodynamics. Interestingly, at that point in time, something like 20 years ago, there was the idea that there was a vasodilating effect from a loop diuretic, particularly furosemide, and Gary was interested in showing this. But what's interesting is he showed the opposite. If you note the second panel in the middle on the top, systemic vascular resistance, interestingly enough it goes up with the use of intravenous furosemide.

I actually use this slide in another way when I show it to our house staff because I'm always hearing the story about the patient who was clearly congested and with pulmonary edema with a blood pressure of 100 and therefore they can't be diuresed because they'll get more hypotensive. And I always say, "Look folks, when you actually give an IV diuretic, it doesn't happen that way. It does remove fluid, but your hypotension if that's what you think you have is not actually going to get worse." Well, it may not get more hypotensive, but you may actually get this vasoconstricting effect that is mediated by plasma norepinephrine and plasma renin activity. These are the two things incidentally that we worry about with chronic use of diuretics and maybe even a risk of acute use because you have this spike of sympathetic activity and activation of the renin angiotensin system. You also notice that vasopressin, which is another vasoconstricting substance, also rises acutely with the use of intravenous furosemide. These things then do resolve over time, and you notice that left ventricular filling pressure also falls. But this is probably one of the best examples of one of the untoward effects of diuretics.

What about vasodilators? And vasodilators then have been nicely gone over by Doug Kirk in terms of things they do. Let me just show you some data. I have to say that all of us in the heart failure world like to say when we are trying to be all so virtuous to each other, that, "Oh, yes, nitroprusside is the thing that we think is the best to use pharmacologically. It has an immediate action of vasodilating both the venous system and the arterial system." So the idea is that the filling pressures would go down as you see on this slide along the bottom on the left, the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure goes down and systemic vascular resistance also goes down, and your cardiac output to some extent goes up.

Unfortunately, though, they're a bit cumbersome to use, and frankly the amount of use that gets done acutely I think is quite low and even chronically outside of most heart failure centers. So pharmacologically this is the most attractive agent to use of the vasodilators because it has an acute onset and acute offset, and it does all the things you would like it to do. Unfortunately, most people don't actually use it. Interestingly, I had to search far and wide to find a slide anymore that even illustrates what it does. And it may interest you to know that this is from an article on the treatment of aortic stenosis with a vasodilator therapy that was also published by Frank Peacock's friends at the Cleveland Clinic a couple years ago in the New England Journal.

How about nitroglycerin? Well, nitroglycerin has a lot of the same pharmacologic activities, but do remember that nitroglycerin doesn't become very active in the arterial system until you've given a lot if it unless you're having a massive effect on filling pressure. And so therefore all of these nice effects that you see are the result of large-scale nitrate doses, and commonly they don't -- people don't use these kind of doses acutely, and I'll come back to that in just a moment.

It is worthwhile saying that the patient who comes in with acute pulmonary edema and they're hypertensive, a very quick way to get the show on the road if you want would be to give two nitroglycerins under the tongue, which is going to give you some kind of systemic effect that will be brief, both on the venous system and on the arterial system.

Now, this is nesiritide, and Doug mentioned to you that nesiritide has been a great triumph of marketing, if you will. There is effective data on nesiritide that involves symptoms to some extent, and also a vasodilating effect. What you see here is the vasodilating effect with a change in wedge pressure in the VMAC trial, and what you see is placebo, nitroglycerin, and nitroprusside. VMAC did meet its primary endpoint, which was an improvement in dyspnea at a 3-hour point, and there was once again with nesiritide an improvement, as you see, in hemodynamics.

Now, VMAC had its controversial aspects, too, one of which was that the nitroglycerin dose was quite low. It was on average about 50 milligrams. There were those who felt it wasn't really a fair comparison of nitroglycerin and nesiritide. It's also true that if you look carefully at the VMAC data, that all three groups had significant improvement in dyspnea, suggesting that conventional therapy of heart failure patients when they come in the hospital in terms of making them feel better is quite effective. This has limited our ability to show things actually work because the therapies we do actually do improve some improvement -- do improve symptoms in patients when you go and measure them.

There has been a signal with nesiritide with worsening renal function, and worsening renal function in most scenarios of heart failure is associated with a worse outcome if the worsening renal function persists. This has been an arguable signal in the nesiritide database, but has worried many and has prompted a large clinical trial called ASCEND, which is ongoing, to look at the long-term effects of nesiritide.

Nesiritide has very much gone out of favor recently for all these reasons. But also I think when people look back at the data, it really wasn't entirely clear that it was all that effective on top of conventional therapy, so these are the two reasons why nesiritide has largely gone out of favor.

What about inotropes? Well, the dirty little secret that many of us in heart failure have is, yes, we do use inotropes on occasion, even though we talk about how bad they are. This is looking at dobutamine and milrinone and is just giving you the notion that both of these agents are effective in terms of improving cardiac index and mean capillary wedge pressure. They're effective agents when we use them in appropriate patients.

However, it is also true there has never been a study that has shown a favorable signal with inotropic therapy in frankly any setting, whether it's acute or chronic heart failure. Acute heart failure has been very difficult to study. This is the OPTIME trial, which was the best attempt to be able to do that, comparing milrinone to placebo in ADHF patients. As you can see here, on outcomes there is no benefit for milrinone-treated patients compared to placebo, and there is a worse adverse outcome profile, which is on the upper part of the screen.

This is unfortunately once again a study where there has been some controversy, partly because the population enrolled is really not the population that most of us would have used an inotrope in anyway. These were relatively mild to moderately sick ADHF patients. They weren't the kind of end-stage heart failure patients or even shock-like patients that we often are using inotropes in, even though we don't want to. So this kind of data doesn't really apply to the patients that we use -- that we are using inotropes in these days and have for some years. We don't have a study on that basis on that group of patients because frankly physicians won't randomize those kind of patients into a clinical trial.

Are there any data or anything in the future that would be helpful? And I'm just going to show you some data that was presented at the American College of Cardiology. This is the HORIZON heart failure study with istaroxime. Now, no one wants to call their drug an inotrope anymore because that immediately is a bad label to put on it, so this is a drug that was called a calcium sensitizer, a lot like the drug levosimendan that had a brief star turn in the United States, but again produced data that was very much like you saw with OPTIME.

A lot of different squiggles and lines on this slide, but good things were happening in terms of hemodynamics with istaroxime in HORIZON-HF, but this is an early phase trial. Dr. Mihai Gheorghiade presented this data, and if you want to find out a little bit more about it, I think he's on the program later today and could talk to you more about it.

But people are looking for something to use in this sort of patient that has a low output and is in shock, and a calcium sensitizer, which is a little different than milrinone, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, or a sympathomimetic like dobutamine, this kind of agent like levosimendan has been attractive to some with the idea that maybe there is not the same kind of adverse event kind of experience with it, but you would still get the kind of benefit we have seen.

Okay. Now what about other things? And this is investigational therapies. And in investigational therapies, one interesting one is the A1 adenosine antagonists in heart failure. This is -- if you think you've seen this slide before, it's because you have, now twice. This is a continuation of the data looking at GFR, furosemide and placebo by Steve Gottlieb. As I mentioned to you, this was really designed to look at an adenosine antagonist, looking at the effect of an adenosine antagonist with or without furosemide on GFR.

BG9719 is this adenosine antagonist, and GFR does not decrease even though urine output is augmented, particularly with the furosemide used in combination with this agent. Now, what's happening here is that when you give a diuretic and you introduce more salt and water to the inside of the kidney, the macula densa towards the bottom of the cartoon on the right, what you find then is that there is a feedback mechanism that occurs, tubuloglomerular feedback is the expression nephrologists always use. That is an adenosine-mediated effect that inhibits sodium reabsorption in the proximal tubule, number 1 on this slide, and also produces vasoconstriction of the afferent arterial, that's number 2 on this slide. And what an adenosine antagonist does then is to impact on these two effects.

The agent that is furthest along in development is rolofylline, and rolofylline is shown here in an early study looking at change in plasma -- in renal plasma flow and change in GFR. And as you can see over time for rolofylline there are favorable effects in both these parameters. There was a pilot study presented at the American College of Cardiology for dose ranging with rolofylline in what is called the PROTECT trial. And this is looking at a primary outcome which is kind of complicated to go through and I don't unfortunately have time to do that. But looking at three doses of rolofylline, and there was a favorable effect on a primary outcome which involved improvement of patient symptoms and a lack of adverse events during a short-term time period, as well as no worsening in renal function, so a dose-related favorable effect on this complicated primary outcome.

Even more interesting are two other things, perhaps. That is to say that for change in creatinine, interestingly if you particularly look out over time at day 7, but more at day 14, there was this inverse relationship between placebo -- now placebo is getting diuretics -- and the dosing of rolofylline so you're seeing a dose-related favorable effect in creatinine over time at day 14. This trial was very careful to look at the fact of what creatinine did over time, not just a one-shot or short-term effect, but looking at day 14 to see whether renal function stayed different as opposed to just a short-term change.

What about 60-day outcomes, was there an early effect that looked favorable? Yes, there was. This is looking at placebo and three doses of rolofylline. And you'd want to look at combined outcome there at the top. Small numbers of patients, but a favorable signal going across the board in terms of the number of patients who had death or cardiovascular or renal hospitalization over this time period. So some very favorable signals with rolofylline in the PROTECT pilot.

How about ultrafiltration? Ultrafiltration is a bit cumbersome to use acutely, as you all know, but certainly for patients who are admitted into hospital, there is some interesting data. This is the UNLOAD trial. UNLOAD looked at two primary outcomes of ultrafiltration added on to conventional therapy: dyspnea or weight loss. As I pointed out to you earlier, it's hard to show convincingly that dyspnea is improved in patients with new therapies, and UNLOAD did not, either, although there was a favorable effect on weight loss over time.

People were pretty interested in that, partly because outcomes in a 90-day period were also improved with the ultrafiltration system. So it was more effective acutely at drawing off weight and also a decrease in clinical events. Unfortunately this was blinded, not a lot of events over this 90-day period, and that's why I put this under the investigational category. People would like to see more data with it, particularly because there was a question about what happened to creatinine over time. There were a number of intervals in which creatinine was actually worse in the ultrafiltration arm.

The last group to talk about is the vasopressin antagonists. Vasopressin is a substance that acts both in the vasculature and on the kidneys. There are V2 receptors within the kidneys, V1 receptors in the vasculature. They go under the term aquaretics, if you will, for their renal effects, where they mediate salt and water metabolism through the aquapurines.

And just very quickly, these agents -- and there are now about four of them that have been investigated -- have shown favorable effects on urine output. This is conivaptan, which is an intravenous agent, and you see a dose-related effect for conivaptan on urine output over time. For an oral agent, this is tolvaptan, and tolvaptan shows a favorable effect on hemodynamics, then looking at change in wedge pressure at three doses.

Now, what about clinical data beyond the just hemodynamics? And the large-scale database that we have now is the EVEREST trial. The EVEREST trial was a brilliantly designed study in that it took a group of decompensated heart failure patients in hospital and looked at both short-term and long-term outcomes. The short-term outcomes are seen in Trial A and Trial B. So the 4,000 patients were basically divided into two 2,000-patient trials and then reconstituted in their original treatment group looking at then the long-term effect of the vasopressin antagonist, which occurred then until a prespecified endpoint went on.

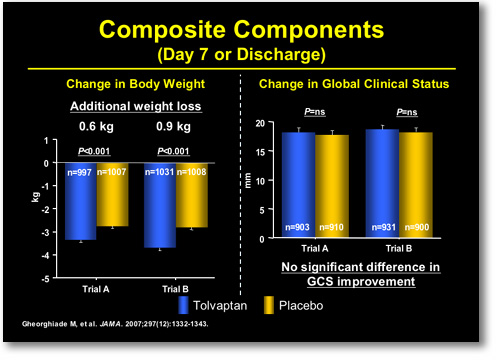

I'm just going to talk to you for a moment today about this primary composite on short-term effect. This is looking at change from baseline at day 7 or hospital discharge on a composite scale of patient global assessment and body weight. It was a combined outcome. Both trials were favorable, both Trial A and Trial B. The part of the composite that was favorable was once again weight loss: The patient global assessment was not favorable. This is what you see here: This is the change in body weight, and this is the change in patient global assessment off on the right (Figure 3). So a little bit like the ultrafiltration data, the effect here was seen on weight loss.

|

FIGURE 3. EVEREST Outcomes at Day 7 or Discharge

|

|

For adverse events, this was a very well-tolerated agent. The vasopressin antagonists do show a change in dry mouth and thirst because this vasopressin is one of the things that regulates when we want to drink water and things and when we don't, when we become hypertonic in our serum -- in our blood solution. But otherwise a very well-tolerated agent.

So to finish up very quickly then, as the other speakers have said that large registries confirm the incidence and prevalence of acute decompensated heart failure, we have very high hospitalization rates of death and rehospitalization. I totally echo Frank Peacock's comments that this has a lot of morbidity, this syndrome: In fact in many cases this is higher than acute coronary syndromes, where we're all running around transferring patients and taking them off to catheterization labs. But somehow acute decompensated heart failure and the importance of what happens to patients is only recently coming into people's eyes as being so important.

Diuretics still are first-line agents, but when initial therapy fails, then modified diuretics. We didn't talk in the interests of time very much about adding on agents like metolazone, although Doug Kirk I think did touch on that.

Torasemide is also an agent that has had some benefit in the diuretic-resistant patients. Adding vasodilators and ultrafiltration we've touched on. Inotropes then we would consider only as a resort in patients with poor ventricular function and decreased perfusion, the sort of shocky type patients with end organ dysfunction. The new agents in development include calcium sensitizers, like istaroxime, adenosine antagonists, and vasopressin receptor antagonists. I'd like to stop there and thank you all for your attention.

|