ADHF Diagnosis & Risk Stratification in the Emergency Setting

W. Frank Peacock, IV, MD

Vice Chief, Emergency Medicine, Medical Director, Event Medicine, The Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH

According to the demographics on heart failure, we spend more as a country on heart failure than any other disease. Heart failure is the number one reason people are admitted to the hospital in the United States. It's the number one reason they come back for a second admission. When heart failure shows up at the hospital, it comes as shortness of breath. It doesn't say heart failure across their forehead. And when you think about shortness of breath, what -- everybody say, "Well, it's heart failure." Well, that's what you get at the end.

When you start, there are a whole bunch of diagnoses; you've got to sort it out. And you have to sort it out quickly, and you have to be right. And I'm going to go through the process. But ultimately we're trying to get to that little slice on the bottom there called heart failure. And one of the problems with heart failure is that it is not a -- it doesn't have one thing, you say, oh, you're done. It is a syndrome. No single test will determine the diagnosis.

Looking at the diagnosis accuracy in the published literature, in primary care the diagnosis has been reported to be falsely positive in over -- in up to 50 percent. And there was another study done in an outpatient clinic where the correct diagnosis was right in 18 percent of women and 36 percent of men on the first time. Now, I'm not picking on primary care. When they show up in the emergency department they're a lot sicker, so it's a lot easier. And you can see that the confounders there are gender and obesity, both of which are common in the United States.

So the first thing we do in the ER is get an EKG, and that's because we're required to get at chest pain in 10 minutes, so everybody's got an EKG. And unfortunately the EKG in heart failure is about useless because it provides long-term prognostic info only -- they'll tell you in five years if the patient has increased QRS duration they'll be dead. But the 5-year outcome does not help the emergency department. So unless there are ischemic changes, the EKG -- we're just done with it.

So what do we do? We do an EKG. We do a physical exam. The physical exam is diagnostic in about a third. That leaves two-thirds of the people out in the cold. We do a chest x-ray. It's nondiagnostic in a quarter, and it also has some significant limitations. We can do other tests -- blood gases and those sort of things that are absolutely useless in heart failure. If you want to know what is the best finding of heart failure, it's the history.

But here's the challenge for the emergency department. What if they're too sick to give a history? I mean, really sick people can't talk very well. What if they speak French? I don't speak French. What if they are drunk? The reality in the emergency department is some of my patients are. And when's the last time you got a great history from a 90-year-old? It's just not going to happen. And what if they're a nut and just want a warm place to sleep, or they're anxious and they just want to talk to somebody?

And what if it's Sunday night? Sunday night's the busiest night in the emergency department, and anybody who works there knows what it's like. This is what it looks like. And the challenge there is I've got seven minutes of patient contact time on Sunday night to get through and make an accurate diagnosis where history is the best. And how much time do you have when they're doing this, when they're laying flat? How good a history can you take?

So the next thing we ask, "Well, how -- are you short of breath?" And they say, "Yes." And if you look at sensitivities and specificities, you can flip a quarter and write on the chart, "It came up heads," and you'll be as accurate as shortness of breath. Shortness of breath is a useless finding in heart failure. It's what they all have. If you look at retrospective heart failure databases, 90 percent will have presented with shortness of breath. But as a predictor of a heart failure diagnosis, it's as good as a quarter.

Orthopnea is the other thing you ask: "Do you get short of breath when you lay down?" And if they do, that has a specificity of 88 percent, so that's pretty good. And sensitivity is useless. It misses a lot. There are plenty of people walking around with heart failure who do not have orthopnea.

The next piece is the S3, the extra heart sounds. So the S3 and S4, and if you remember from your early physiology, they come in diastole, and what you're looking for is the early diastolic extra heart sound. The advantage of this is when it's positive it's very helpful. The S3 has a specificity of 99 percent with a stethoscope. You can take it to the bank. The problem is that in an ER environment, you've got the drunk next door who's screaming about his mother and the kid down the hall, and you can't hear. And that's why the sensitivity is 20 percent.

We miss four out of five S3's. There is some new technology that allows us to do that better, and I'll show that to you in a minute. Rales, we all listen for rales. The problem is in old people, rales are very common, so the sensitivity is once again as good as a quarter. When they're there, they're helpful; when they're not, they're not very good at all.

And next, are there really good findings of jugular venous distention (JVD). You look at the specificity is 94 percent. If you can see JVD, you can take it to the bank. Probably a really good chance the patient has heart failure. The difficulty is we're in the middle of an obesity epidemic, and that's the big confounder for JVD. So the sensitivity runs about 40 percent. It's worse than a quarter. So when it's there it's helpful; when it's not there you don't learn anything.

And the last piece is edema, which sort of is considered the harbinger of heart failure. Look at the numbers. It's the 60-60 club: neither sensitive nor specific. There are plenty of people who show up in the emergency department, especially in the summer, with big feet. And your answer is they're big feet.

So here's the chest X-ray data. It's an extremely blunt tool. It misses 20 percent, one out of five, of echocardiographically proven cardiomegaly. All you have to be is a little bit turned and the heart doesn't look big anymore. And it misses a third of pleural effusions if they're done supine. How do you do chest x-rays in sick people? They lay on the bed: You take their chest x-ray. They do not stand up and get a good PA and lateral. If you do them portable, it's even worse. And reality be told, we do most of our chest x-rays portable because they're sick, and they don't want to -- the nursing staff and I don't want to take them down the hall. And they're hooked to all that spaghetti, and they're on the IV and the monitor, and it's just -- so we do them portable and miss a bunch. So now I'm 15 minutes into my case, which is all the data that I'm allowed to have because that's all you can get back in 15 minutes. I want to show you the time-dependent accuracy.

We just finished a study of 1,000 patients in the emergency department. Fifteen minutes into the door they asked the doc, "What have they got?" The gold standard with two cardiologists at the end of the visit, five days later, and we looked at 30-day follow-up. An emergency doc was accurate in the first 15 minutes in a third. With history and physical, we missed two-thirds. And so that becomes real important for treatment.

In a study of 8300 patients transferred to the hospital by EMS, ultimately 500 were shown to be heart failure. And they got nitroglycerin, morphine, and furosemide. Now, I'm going to rant and rave about morphine. I think it's a terrible drug. It doesn't have any role in heart failure. However, this was a study done in 1992, so it was the standard of care. So 240 people got treated, and if they got treated it took an extra two minutes in the ambulance to treat them. And if they received -- if they had heart failure and they received treatment, their odds of survival was a 250 percent increase. Early treatment absolutely works. We should all do it.

Here's the scary part. There were 106 of those patients who ultimately got treatment turned out not to be heart failure, and their mortality went from 3.8 percent to 13.6 percent. So if you have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and you get heart failure treatment, it's not cool. And that's a 250 percent increase in mortality. So if you're right there's a 250 percent increase in survival, and if you're wrong there's a 250 percent increase in mortality. So there's a two-way sword that you'd better be quick and you'd better be fast -- and you'd better be accurate.

We're 15 minutes in our case, and that's about the time the B-type natriuretic peptides (BNP) can come back. And what you see here is BNP synthesis. On the right side of this is proBNP. It's released in the wall stress of the myocardium. It is the N-terminal proBNP, or BNP. There are assays for both of those, and they are very accurate for ruling out heart failure. On the left side of this graph represents ANP levels. And if you're a fish in the water, you can see the ANP level's about 800. And think about it, that if you live in a salt water environment, you've got salt water leeching into you all the time, if you don't pee salt water, you're going to drown. It seems crazy that fish would drown. And it doesn't because it's got a ton of natriuretic peptides.

But as you move up the evolutionary scale to amphibian and reptiles, you can see those ANP levels drop. So by the time you're a mammal there's only two times in your life your natriuretic peptide levels should be up, and that is during birth, as you shift from fetal to adult circulation, or pathologically. And that's why we can use it as a diagnostic. Conversely, renin is the darker yellow there. It goes up as you move up the evolutionary scale, and the reason is because we're out of the water. We walk around. We need to hold salt water inside of us. If we lose it, we'd be dehydrated to death.

When you look at BNP levels by diagnosis, you can see that in heart failure, it's about 1,000, whereas people who had COPD it was about 86. So a great discriminator early in the course. If you look at accuracy of physician assessment -- this is a receiver operating characteristic curve -- and if you look at the red dot in the left upper corner, that is where the perfect test would go, would be aligned. So you want to be as close up to that dot as you can. And the red line is doctors with their clinical judgment, and the blue line is doctors considering NT-proBNP. So what you see is that using natriuretic peptide gets you closer to that red dot. So this is the function of it. It's a better test for the patient.

I'm going to talk a little bit about mortality. This is BNP levels at the door. This was published by Gregg Fonarow and me about three months ago. And what you see, the higher the BNP level in that top graph is 1700, the mortality this week -- this is not five years from now -- the mortality this week is 6 percent. What does that look like in terms of your hospital? The death from a myocardial infarction in most hospitals is 4 percent. This is 50 percent higher. So if you have a big high BNP, you need to worry about that patient. BNP can be confounded by two things. One is renal failure. And what this is, is as you go across this graph from left to right, when you get to the right side, the kidney is essentially dead. That's a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) less than 30. And you can see that in both of the groups, with and without heart failure -- without heart failure is the little orange ones, and the tall ones are with heart failure -- that it goes up, so the more your kidneys are dead, the higher your BNP.

There's a big discrimination between these heart failure and non-heart failure populations. And we use a cut point of about 200 for BNP to say, "Well, even though they have some renal insufficiency, they still cannot be ruled out for heart failure." The other one is obesity. If you have a body mass index greater than 35, your BNP will be falsely low. This is really important. So you see somebody who's 350 -- I work in Cleveland. We have a huge obesity problem. So you see someone who's 350 pounds, their BNP will come back and it'll be 200. And they look exactly like heart failure. And the answer is, they are. Because it's markedly decreased in the setting of high BMI.

The point being here is there are two things you can do. You can either double the cut point or double the BNP level. That's what I do. If it comes back at 200, I say, "Well, it's actually 400" in people with a high BMI. So this is how it turns out when you're all said and done. This -- if you look on the left here, we can say that patients with a BNP less than 100 or an NT-pro less than 300 are very unlikely to have heart failure, less than 2 percent. You need to think of a different diagnosis causing that patient's shortness of breath.

If those are higher, if the BNPs more than 500 or the NT-pro is greater than 900, heart failure is very likely, and you can initiate treatment. In the gray zone -- 1- to 500 BNP and 3- to 900 for NT-pro -- you've got to work it out. You don't have a clean answer. You need to do a chest x-ray. You need to do a Q scan or CT angiogram, or do something additional -- get an echo -- to figure out what the diagnosis is.

When you use these markers for accuracy, what you can see here is we take the misdiagnosis rate, which in this on history and physical in this study was 25 percent, and you add BNP to it, now the misdiagnosis rate is 18 1/2 percent. We're not done, but it gets us right down there to where we're wrong only one out of five times.

Now, this is a new device that's out. It's called the AUDICOR. And what it does is to substitute a microphone for the V3 and 4 leads in the EKG. You still get an EKG, but it allows you to use some digital technology. You hear the heart sound. And then you can look at the box on the right is the actual tracing itself, and it says S3 in that little wiggly line. And I don't make any pretenses that I can read these wiggly lines, but if it says S3 in the box in the middle at the top there, then you know that patients has an S3. And this does a lot more sophisticated sound analysis and it's a lot better at reading that background noise than I am.

When you look at the presence of an S3 versus left ventricular and diastolic pressure, the louder is the S3, the higher is the left ventricular and diastolic pressure, in other words, the harbinger of heart failure. The thing you need to know is that the S4, in the dark purple there, is much more common as you get older. This is age across the bottom. The S3 disappears. So when you're 28, you might have an S3. It happens in about a third of patients. But by the time you're in the heart failure years, you're 50 or 60 years old, an S3 is not a common event. It happens in less than 5 percent of patients.

The BNP is sensitive -- BNP under 100 is highly sensitive (95 percent). The specificity is only 64 percent, so not the greatest for ruling in. ItŐs a great test for ruling out HF at low levels, but if you add a BNP that's really high, now you're at 93 percent specificity. So the message here is that the BNP is really good when it's a low level rule-out, but we need something specific to add, and that's where the S3 comes in.

Sean Collins and I looked at several hundred patients -- about 400 in total when we were done -- but this is the analysis done in 133. And we said, "Well, let's see where the ER call it heart failure and the -- or the ER said there wasn't heart failure and the final diagnosis five days later that says it was." And we ended up with 44 patients out of the total in that box there. We went back and looked at those 44, and 15 of them had an S3 that we didn't hear. And the point of that is if we would have known, we could have done the right thing for the patient: admitted them in the hospital, but as well started treatment.

When we went back and looked at those misses themselves, what it was, there was a three times incidence of COPD, that I called a COPD. All these patients had lower BNPs, so they were in the gray zone, which was the challenge, and they stayed in the hospital a day longer. So there's a penalty for missing the early diagnosis. If you want to put this in terms of likelihood ratios, BNPs under 100, you're done, the likelihood ratio is .1, and that means you do not have heart failure. If you go into that BNP gray zone between 100 and 500, you can see the likelihood ratio is 9, and that gets you into the area where you can start considering treatment. So the gray zone disappears.

I'm going to talk a little bit about risk stratification. One of the controversies in heart failure is troponin. Everybody says, "Oh, troponin doesn't mean anything. It's always elevated in heart failure patients." And I want to disabuse you of that. This is an analysis of 14,000 patients that we did with positive troponins. And what you're looking at here is that if the troponin is positive at presentation, the mortality is 8 percent. That's twice of a myocardial infarction. If the troponin is negative, it's about 2 1/2 percent. More people intubated, they stay longer in the hospital, they stay longer in the ICU.

An elevated troponin in the setting of heart failure is evil. It is not a normal thing. And the higher it is, the worse they do. And this is -- you use both troponin I and T, in different colored bars. The point is you can see the shape of the curve: The higher the troponin, the worse they do. And this is the Kaplan-Meier curve. This is the death per day, and it separates at one day. So this is an acute, evil marker of death in a heart failure patient. This is coming out in the New England Journal in about two weeks.

Troponin can be used with BNP. If you look at the BNP being low and the troponin low, the risk of death is 2 percent. If both are high, the risk of death is 10 percent, and then in the middle it's about 4 1/2 percent, either one being elevated -- and elevated here was considered greater than 840 on your BNP -- and the troponin was positive, meaning it wasn't zero.

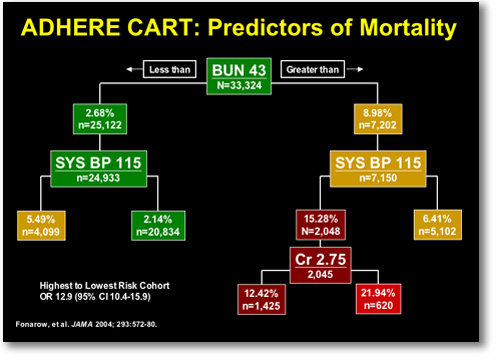

The other important piece is renal function. This is the ADHERE CART analysis (Figure 1), where they stratify patients by what is the most important predictor. Everyone said, "Oh, it's troponin, it's injection fractions, age, it's something else." It's actually blood urea nitrogen (BUN). If your BUN is greater than 43, your risk of death this week is about 10 percent, that box on the right. And if you add to that a systolic blood pressure of 115 or lower, your risk of death is now about 15 percent, and an elevated creatinine, it's 22 percent, one in four dead this week.

|

FIGURE 1. Predictors of In-hospital Mortality in the ADHERE Registry

|

|

Renal function becomes critical. And I'll tell you right now that patients in your hospital, the BUNs are 50 on a regular medical floor. And my opinion is that is not right. If your BUN is up that high, you should be getting aggressive care because that's a death rate twice of a myocardial infarction. And your CCUs are full of people with lower death rates.

This is what we do at my hospital. You show up at the door, age greater than 40 and asthma not clearly present. You automatically get an EKG, a troponin, and a BNP. They're all done at point-of-care. By the time I see that patient 15 minutes later, I'm ready to make a decision. I talk to them for a few minutes, and we're done. If they have a BUN less than 30 or blood pressure greater than 160 at presentation -- these come from a couple studies that show these people do very well. They go home in 24 hours. They don't die. They don't come back within a month. Or if the BNP is less than 500, that's the low-risk group. Now, we may keep them and hold them overnight and take a couple liters off of them, but this is a low-risk group. They do well. BUN greater than 43, low blood pressure, high creatinine, these people do terrible, or BNP greater than 1700. They should go to a unit and get aggressive care. And the S3 in the middle if you have it pushes you to the right, as well. So you're left with a little group in the middle, that's your gestalt group. We don't have that completely worked out. But we certainly have the parameters to pick out heart failure and make a decision where it goes.

In Summary; heart failure is a hard diagnosis. Errors are common. They are time-dependent. The longer I have the patient, the more accurate I am. The problem is that the longer I have the patient and they're not getting treated, the patient's not benefiting. We've got to be fast, and we've got to be right.

|